EPISODE: 40

By THAN HTUN (GEOSCIENCE MYANMAR)

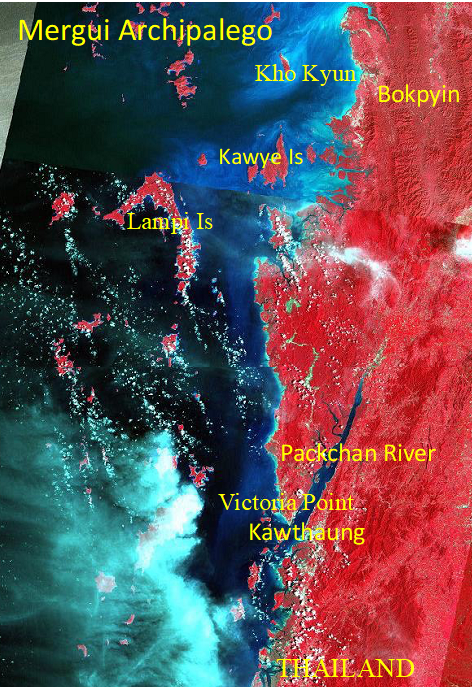

Mergui Series

This article continues from Episode 39, titled ‘The Geology of Mergui District,’ contributed by Sethu Rama Rau in 1930.

Relationship of the Moulmein to the Mergui series

The isolation of the limestones of the Mergui series in an alluvium-filled valley has so far prevented the establishment of their relationship to the underlying Mergui. There is little doubt that they are unconformable, but the evidence is insufficient to establish this as a definite fact. The outcrop of the limestones at a source of Kyaukpya Chaung, north-west of Peinchaung village on the Mergui rocks, may perhaps be an obscure instance of an unconformable junction.

The Red Sandstones

It is familiar to everyone that biotite granite yields a reddish sandy soil by weathering, the red colour being due to iron oxides liberated by the decomposition of biotite. Many tin and wolfram mines worked in the Tavoy district on the Myitta road, exposing sections that show the weathering of granite on reddish soil. Some of the sandstones have a few concretions of oxide of iron, and the bedding planes of the sedimentary rocks are coated with a thin layer of limonite. The red colour of the sediments of ‘The Red Sandstones’ may have been caused by the oxide of iron carried in solution from the decomposition of biotite of the granite and from the ferruginous concretions and the limonitic layers of the sedimentary rocks.

The rocks of the Red Sandstone series are made up of the following in descending order:

IV. Purple sandstones, shales, and conglomerates.

III. Fine-grained pinkish sandstones and shales with patches of white clay.

II. Calcareous sandstones.

I. Conglomerates and grits.

Of these, the last occur on the Pataw and Patit islands, off the coast near Mergui town. The first three are exposed in the chain of islands, commencing with Gladys Island and Kyunzauk in the north of Panadaung Taung and Thityawa Islands in the south. The Dorcas, Kataungbyo, Kyunbon, and Satkyun islands in the middle of the chain are made up of similar rocks.

Although the general strike of the rocks of the Mergui series is nearly 20° W of N – 20° E of S, the beds of the Red Sandstone series strike 20° E of N – 20° W of S and dip in a direction 20° S of E.

The grits and conglomerates of Patit Island were unsuccessfully searched for fossils. There are many infiltrations of silica in the joints of these rocks, which resemble fossil wood. A specimen under rock register Nos 34-734 of the Geological Survey of India is of such an infiltration. Dr Dudley Stamp has collected silicified fossil wood and impressions of partly carbonized wood. The quarries opened by the Public Works Department for the Mergui Port works have exposed many sections showing the sandstones and grits resting on the denuded edges of the argillites of the Mergui series, as seen in the southwestern corner of the island.

It may be stated in this connection that similar ‘Purple Sandstones’ comprising soft sandstones, shales, and hardened clays of a dark brick-red or chocolate colour were observed by Mr Middlemiss in the Southern Shan States. Dr Noetling has described ‘red sandstone of undetermined age’, resting on the blue limestones in the Gokteik-Kunlong valley east of Thibaw; Mr Latouche refers to dark red sandstones, with a purplish tinge among the rocks of Namyau series in the Northern Shan States, which have been assigned to the Jurassic period. Dr Cotter has mapped red sandstones in the Amherst district and collected a few very poorly preserved fossils, mainly unidentified lamellibranchs. The ‘Red Sandstones’ of Kalaw and the coal measures of Loi-an were examined by Dr Cotter, and the plant fossils collected by him probably belong to some part of the Jurassic or Rhaetic and are consequently Upper Gondwana in age. The ‘Red Sandstones’ have been given a Jurassic Age by Dr. Cotter. Similar rocks also occur in Tonkin, in Southern Siam.

The Tertiary Series

The Tertiary rocks were deposited in valleys corresponding to the present-day valleys of the Tenasserim, Lenya, and Pakchan rivers and carved out by sub-aerial denudation of the rocks of the Mergui and Moulmein series upon which consequently they lie unconformably. The Tertiaries dip at a low angle while underlying rocks are steeply inclined. Isolated islands made up of rocks of the Mergui series surrounded by Tertiary rocks of variable thickness are common features in the deposits of the Lenya River valley. Though the Tertiary deposits of the Tavoy and Mergui districts, extending over a length of more than 220 miles, appear as disconnected outcrops, they were originally a continuous belt, which has been broken up by the post-Tertiary crustal movements and denuded away by the rivers. The old river valleys correspond generally with the present courses of important rivers of the district, and these coincide with the general line of strike. The Theinkun valley, where Rao Bahadur M Vinayak Rao examined oil shales and Tertiary deposits, is situated a little east of the main line and possibly marks the limits of the original deposits.

The Tertiary rocks are chiefly composed of finely laminated shales, sandstones and conglomerates. The chief outcrops are restricted to the river valleys and may be grouped as follows: –

I. The Tenasserim Valley deposits

II. The Theinkun Valley deposits

III. The Lenya Valley deposits

IV. The Pakchan Valley deposits

The formation may be divided into an upper and lower group. The lower group is made up of soft, sandy white shales with plant remains, ferruginous sandy shales with ripple marks at the base, and black carbonaceous shales with thin, irregular layers and lenses of lignite. Resinous lignitic coal is exposed at the top of the lower group. The upper group consists of white or grey, soft, friable sandstones, followed by a ferruginous brown variety. The topmost beds are gravels with white vein-quartz pebbles, associated with a ferruginous conglomerate containing boulders and pebbles of argillites of the Mergui series.

The Tertiary sediments of the Great Tenasserim Valley west of the Thabawleik have been eroded, leaving only a few isolated exposures. Recent and older alluvium has covered these eroded valleys.

In the Lenya River valley, the lower group is well-exposed near the confluence of the Palaw Chaung with the Lenya River and the higher one near the villages of Htawphan, Bonkun, and Nanka Hprao. The thickness of the Tertiary strata of this area may be roughly estimated at 500 feet. The beds strike generally in an N – S direction, changing to 30° W of N – 30° E of S corresponding more or less with the general strike of the country. They dip at low angles of from 3° to 5° in the centre of the valley, rising to nearly 30° on the flanks. The maximum dip of 35° is seen at Palaw and Wanke Hprao. The strata are folded, as can be seen from the varying dip directions. The junction of the Tertiary rocks with those of the Mergui Series is not well exposed, but the abrupt junction makes one suspect either a fault or an unconformity; the latter is more probable. The Pakchan River valley is another example of the removal of the older deposits by denudation and the refilling of the valley with alluvium. This valley is situated along the line of strike of the Tertiary strata of the Lenya and Tenasserim valleys. Near the village of Pakchan, ferruginous sandstones and gravels with white quartz pebbles, resembling the gravel beds of the Lenya River, are well exposed. These are not horizontal but show gentle dips.

The Tenasserim Valley

Mr P N Bose examined the Tenasserim Valley and proposed the name of ‘Tendau series’ for the Tertiary deposits of the area (The village of Tendau (12° 6’; 99° 4’) is situated 19 miles north-north-east of Tenasserim. These consist of shales and sandstones, with coal seams below and conglomerates above. The workable coal deposits of the district occur among these beds and are described under ‘Coal’. The shales are variously coloured from greenish-white to black, the darker colours being indicative of the proximity to coal. The shales are well exposed on the western side of the river, thin out to the east, and ultimately disappear. Superposed on the shales are conglomerates with interbedded sandstones. The conglomerate is coarse, and the pebbles, which sometimes measure one foot in diameter, are subangular in shape. They consist mostly of argillite and slate from the Mergui Series. The interbedded sandstones are massive, soft, and false-bedded. Mr P N Bose observes that the deposits are of shallow-water origin, that they were laid down in a lake-like expanse and derived from the disintegration of the adjoining rocks.

The strike of these rocks is N E – S W with dips ranging from 20° to 40°. The ‘Tendau beds’ have been disturbed to form a syncline, those on the western side of the river dipping eastward and those on the eastern side dipping westward. They rest unconformably on the Merguis, which dip at greater and more variable angles than the Tertiary beds. (A M Heron’s unpublished note on coal written in 1919 has been omitted).

Oil Shales

The upper Tertiary beds exposed along the Lenya Valley resemble the ‘Mepale’ oil shales of the Amherst district in many respects. They are made up of greenish shales, buff sandstones, and sandy shales. Their origin is similar to that of the above shales; they are freshwater sediments deposited in a basin surrounded by argillites and quartzites. The strata are folded into anticlines and synclines, the topmost beds being gravels composed of white quartz pebbles. Plant fossils were observed in the greenish shales of the Lenya Valley but were not sufficiently well preserved for identification. Those collected by Dr J W Gregory in the Amherst district were identified by Mr W N Edwards, who assigned a later Tertiary age to the oil shales there. To the beds of the Lenya Valley may perhaps be ascribed an Upper Tertiary, most likely a Pliocene age. The shales exposed near Bonkun (11° 18’; 98°57’30”) and Htawphan on the right bank burn with a bright flame, emitting odorous fumes when heated in a Bunsen burner; they cannot be ignited with a match. These shales would correspond to the low-grade oil shales, those approaching the ‘barren shales’ referred to by Dr Cotter; they could not be worked economically on account of the small extent of their outcrop and their poor quality.

Rao Bahadur M Vinayak Rao has examined the oil shale outcrop of the Theinkun Chaung. The oil shales exposed in this valley are of a laminated dark-coloured variety, passing down into light reddish shales. They dip about 15° in an N N E direction. The tertiary beds of Theinkun Valley are more than eight miles long, with a width of about a mile and a half. The valley is difficult to access, as one has to go from Letpanthaing to Theinkun in small canoes or dug-outs. In the event of a railway connection being established between Burma and Siam along this route, the oil shales could be worked. Dr Helfer has referred to this locality as one of the coal-mining areas.

Volcanic Rocks

Volcanic rocks are represented by fine-grained dark-coloured olivine basalt, well exposed on Medaw Island. Except for a narrow strip of sandstones and grits exposed near Tawbya, the major portion of the island is covered by olivine basalt with a thin cap of laterite. The basalt is in the form of a flow and lies on rocks of the Mergui Series. It consists of two portions, a main sheet and another smaller one to the east, and sandstones of the Mergui Series occupy the intervening area. Mineralogically, the basalt of the two exposures is identical. Although a careful search was made, nothing resembling volcanic vents or necks could be seen. Hand specimens of fresh rock show unaltered crystals of olivine. Two varieties of basalts are present on the island. The usual compact variety without amygdule is restricted to the outskirts of the flow, coinciding with the coastline, while the amygdaloidal type is found in the centre of the flow in the middle of the island. It is difficult to fix the age of these basalts, but they may be tentatively ascribed to the Tertiary period and associated with the volcanic outbursts of Upper Burma. They are the most southerly occurrence of volcanic rocks in Burma.

References:

Sethu Rama Rau, Rao Bahadur 1930: “The Geology of the Mergui District”, Memoirs of the Geological Survey of India, Vol LV, Part 1.