EPISODE:38

By THAN HTUN

(GEOSCIENCE

MYANMAR)

Sethu Rama Rau

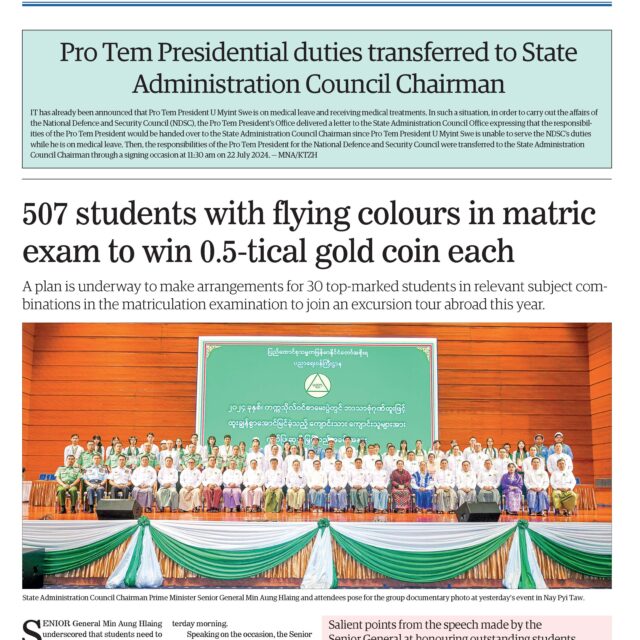

Sethu Rama Rau was a distinguished senior geologist with the Geological Survey of India (GSI), renowned for his extensive fieldwork in the Burma Circle. According to GSI records, Sethu Rama Rau continued mapping the Tertiary beds west of the Irrawaddy River in the Minbu and Pakokku districts. He completed the survey of the area covered by sheets 84K/11 and 84K/15, except for the portion already surveyed by Mr Cotter. Sethu Rama Rau returned to headquarters from the field on 31 May 1908. He was then assigned to Mr Pascoe’s party in Burma and departed for the field on 27 October 1908. He returned to headquarters on 18 May 1911, rejoined the Burma party, and left for the field on 27 October 1911. Sethu Rama Rau returned to headquarters on 12 May 1912 and was granted a one-month and thirteen-day privilege leave starting 2 September 1912. He returned from leave on 15 October 1912, rejoined the Burma party, and departed for the field on 8 November 1912.

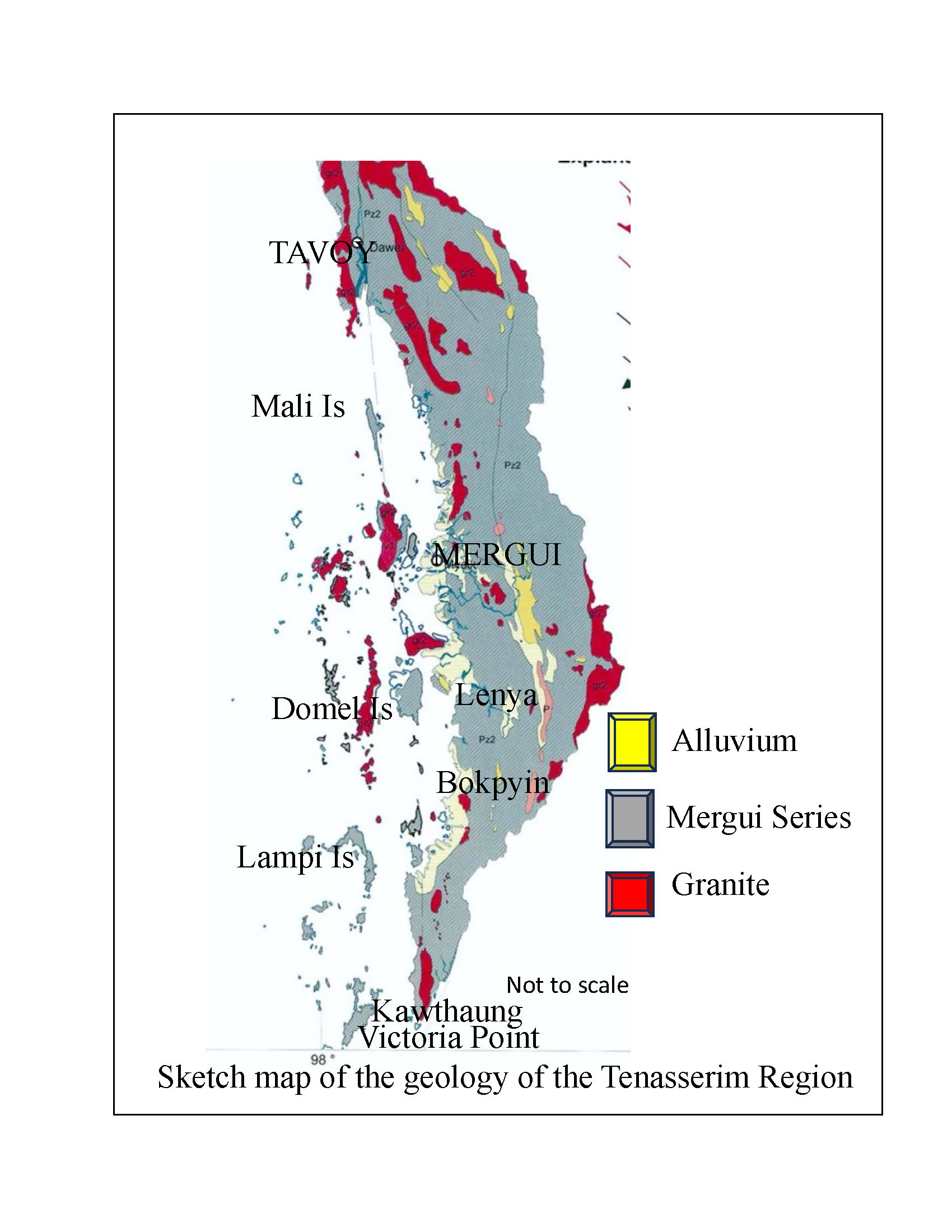

The systematic survey of Tavoy and Mergui was continued by a team consisting of Messrs. Coggin Brown, Heron, Sethu Rama Rau, and Vinayak Rao. By the end of 1919, the map of Tavoy on the scale of 1 inch to 1 mile was nearly completed, with only a small area of extremely inaccessible terrain remaining to be surveyed. Due to the increased attention now being paid to potential tin-bearing ground, work has accelerated in Mergui, both in the outer ranges and in the Tenasserim Valley. Sethu Rama Rau passed away in 1929, and his report, “The Geology of the Mergui District,” was published in 1930. The concise account of his report is as follows: –

The Geology of the Mergui District

The geological survey of the Mergui district was the outcome of the operations to increase the output of wolfram for munitions during the War. On the completion of the geological survey of the Tavoy district, the systematic mapping of the Mergui district was taken in hand in 1918 and completed in the year 1925.

The map on the scale of four miles to an inch has been reduced from the original one-inch standard sheets surveyed by Dr A H Heron, Rao Bahadur M Vinayak Rao, and the author. The published and manuscript reports of these officers have been made use of in this paper, as well as reports and maps by Mr J J A Page, late of the Geological Survey of India, who examined the tin mines of this district and surveyed many of the islands of the Mergui Archipelago. His reports have been freely used in the preparation of the paper and its maps.

Since 1838, many observers have described various mineral occurrences in the Mergui district, and some of the information contained in the following pages has been derived from 46 published reports of the various GSI geologists from 1838 to 1926.

Physical Features

The Mergui district, the southernmost district of Burma, extends on the mainland from the Myinmoletket mountain on the border of the Tavoy district in the north to Victoria Point at the mouth of the Pakchan River in the south and from the hill range forming the Siamese frontier on the east to the sea on the west, and include the islands of the Mergui Archipelago.

Mountains

The chief hill ranges lie in an N W – S E direction, coinciding with the strike of the sedimentary rocks of the district. The main rivers drain the valleys lying between, and the plains are restricted to the sea coast and the banks of the rivers. The Myinmoletkat peak, rising to 6,800 feet on the border of the Tavoy district, is the highest point southwards; the altitude gradually decreases to 1,000 feet north of Victoria Point.

The range of hills forming the continuation of the ‘Central Range’ of the Tavoy district is represented by the granite peaks of Mo-taung, Ne-thi-taka-kye-taung, Pondaung, and Mau-taung, rising to heights above 3,500 feet; it is the southern extension of the Myinmoletkat range, and crossing the Tenasserim river reappears on its left bank. On the right bank, it is composed of a core of granite with sedimentaries on its flanks. The Wabyauk taung, with an average altitude exceeding 2,300 feet, marks the divide between the Palaw, flowing west, and the Tenasserim rivers. Further south, as far as Maliwun Peak, the general altitude is about 2,000 feet. The granite spurs of the Tamok, Mayinbingyi, Wabyauk, Tagu, Cheyadaw, Yanngwa, Karathuri, and Maliwun taungs, and the Manoron, Htapten, Htongdon taungs, consisting of sedimentary rocks, mostly quartzite and slates, from the prominent features of the country in the south. The easterly range, corresponding to the ‘Frontier Range’ of the Tavoy district and forming a continuation of it, is situated on the left bank of the Tenasserim River and is made up of granite from the northern boundary of the district up to the sources of the Theinkun Chaung.

Rivers

The Great Tenasserim River takes its source in the Tavoy district and flows southwards in a narrow valley as far as the town of Tenasserim, where it joins the Little Tenasserim. The Theinkun and the Ngawun Chaungs rise in the granite ranges on the Siamese frontier to the southeast and flow in a northerly direction to form the Little Tenasserim. The united stream then flows westwards for some distance and again takes a northerly course till it bifurcates into the Kyaukpya and Tenasserim branches. The river is navigable for country boats with the help of the tides up to the village of Tagu during the dry season and up to Tharabwin during the rains.

The Lenya River takes its origin in the eastern hill range forming the boundary with Siam, and flows in a northerly direction for a distance of sixty miles up to the town of Lenya; it then takes a westerly trend till it joins the sea near Shwegenyo, excavating its channel through the western hills. This river is also navigable for small country boats, and the action of the tide is felt as far as Bonkun. The Pakchan River rises in the same range of hills as the Lenya River but has a southerly course for nearly 80 miles till it empties into the sea near Victoria Point. Cargo boats of small size can sail up to Pakchan with tides, and small launches can reach Maliwun without difficulty.

The Palauk River rises in the frontier hills of the Tavoy district on the slopes of Myinmoletkat peak and flows south-westerly down to the village of Kataungni. It then continues westward till it joins the sea. The upper part of the valleys of this river and its tributaries, from their source up to Kataungni, contain both tin and wolfram mines.

The Palaw River gathers its drainage waters from the western slopes of Kyunshe Taung and Kyaukthin Taung, lying west of the Great Tenasserim River and flows in a nearly northern direction up to Zadiwun village. The course of the river then takes a westerly trend till it meets the sea near Palaw. The tides reach up to Palawgon, and country craft can sail up to that village. The upper course of the Palaw River near Zadiwun and that of the Impo Chaung near Ninwin and Migyaungthaik flow along the mineralized zone, and many tin mines are situated in this belt.

Coast

The Mergui Archipelago stretches down the entire length of the coast, consisting of 804 islands, which are mostly hilly and forest-clad. The formation of islands is proceeding even today with the help of what is known as a galet — a Burmese word for a very narrow strait connecting two arms of the sea and dividing two islands. Tidal waves and marine erosion work on the rocks at the source of two streams flowing in opposite directions on the saddle-like ridge between them till they are base-levelled. Later, the channel is deepened, and a regular connection is formed, through which small boats can pass only at high tides. At low tide, the ridge of the strait is either dry or covered with shallow water. Such galets are many and range in width from ten to hundreds of feet. They are numerous off the coast of Karathuri, in the Cambell islands, the Selondaung Chaung Islands, near the Yamon, Pedaing, Lethit, Kyaukmo and Ahyin Chaung, south of Mergui town and in many other islands.

Lying off the coast, there are many large and small islands made up mostly of indurated rocks of the Mergui Series, i.e. agglomerates, quartzites, and slates. There are traces of islands composed of biotite granite, which are, doubtless, summits of a submerged continuous batholith. A group of small islands south of Ross Island extending from Warden’s Island to Court’s Island, and the long line of islands extending from the Pickwick group through the Domel islands southwards to High Island, are composed of granite, which may be in submarine continuity with the boss of Ross Island. The line of islands from Pulo Dana to Pulo Sum is another instance of the above. North Cone Island (11° 8’; 98° 36’) and South Cone Island, and some others north of Pulo Dana, are small in size and conical. Others are rounded and flat, rising a few feet above sea level, the habitations of Malay and Burmese fishermen. Most of the islands are inhabited, but one sometimes finds fresh drinking water and groves of coconut palm fringing bays, marking the position of a deserted village. The coastline is never straight. Large islands, such as the Kissering, Domal, Sullivan, and Forbes Islands, have indented coastlines forming a series of bays with intervening promontories, which afford shelter to boats during stormy weather.

The coastlines of the mainland and some of the islands are fringed by extensive flats of soft mud exposed for miles at low tide and submerged at high tide. These merge gradually into mosquito-infested swamps, marshes, and low-lying fields, which are sparsely inhabited by Malays, Shans, and Burmans, whose principal means of livelihood is fishing. It is common in exposed situations to find the steep rocky slopes being denuded and disintegrated at their base by the waves. In the outer islands, the coast is usually a sandy beach, but that of the mainland consists generally of laterite.

Changes of level

The coastline adjoining Maliwun and Champang, including the bays, mangrove swamps and galets, the alluvial flats of the Palaw, the Lenya, the Pakchan, and the Tenasserim rivers, and some of the areas shown as ‘submerged periodically’ on the maps, mark the position of a belt of the country which was once submerged under water and formed part of the estuaries of streams. The Palaw valley is filled with recent alluvium, with a few conical hillocks; rounded and water-worn pebbles of quartz occur at the base of the latter. On the eastern and western slopes of the Maliwun range near the villages of Maliwun and Champang, rounded hillocks covered with lateritic soil are exposed at a height of about 50 feet above the present sea level. The coastline from Kalagyun Island in the north to Bungel Baleingyi shows many boulders of laterite. Further, extensive mud flats, covered with soft mud and submerged at high tide but exposed at low tide, occur on the coast west of Bokpyin and Karathuri. All these facts afford evidence that the present coastline was once submerged and has been raised above the water during sub-recent times.

Geological formations

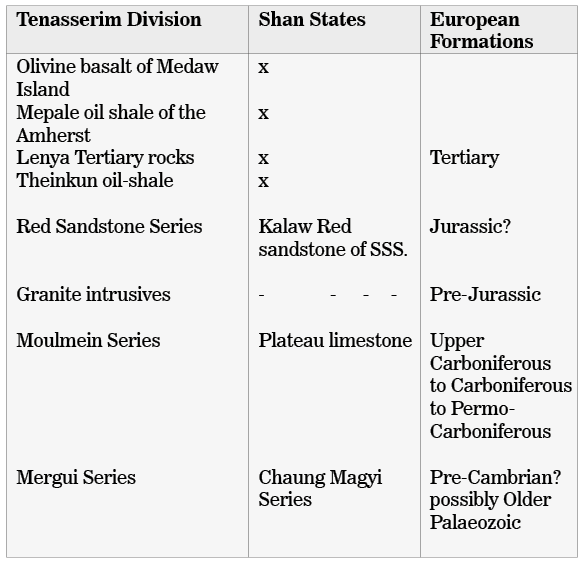

The following table gives an approximate correlation of the formations found in the Mergui district and their probable age.

References:

Sethu Rama Rau, Rao Bahadur 1930: “The Geology of the Mergui District”, Memoirs of the Geological Survey of India., Vol LV, Part 1.