By Yin Nwe Ko

It took less than four hours for nine jurors to reach a verdict. On December 11th in a San Francisco courthouse, they unanimously agreed that Google’s app store was a monopoly and that the company had engaged in anticompetitive behavior. The decision strikes a blow against the search giant, which is concurrently embroiled in other legal battles. It may also redefine the app-store economy.

Most smartphones run on one of two operating systems. Apple’s iOS is a walled garden with just one app store — its own. Other device-makers tend to use Google’s Android, which on paper lets in app stores other than the Google Play store. The case was about whether it does in practice. In 2020, Epic Games, a game studio, urged players to use its payments system to make purchases in “Fortnite”, its blockbuster shoot them up. The idea was to bypass the 30 per cent cut taken by Apple and Google on most in-app purchases in their app stores. “Fortnite” was briefly banned from both.

Epic sued. Its lawyers argued Google was stifling competition by striking deals with, among others, smartphone makers, such as Samsung and LG, to give the Play Store prime placement on their devices in exchange for a cut of revenues. The jurors did not buy Google’s defence because it competes fiercely with Apple and other app stores on Android devices.

So far, so straightforward. What makes the situation strange is that the verdict is at odds with the one in Epic’s near-identical case against Apple. That concluded in 2021, with Apple winning nine out of ten counts (on the tenth, related to the use of alternative billing systems, it lost).

One reason for the difference may be that a jury, not a judge, decided Google’s fate. Public opinion is sceptical of big tech, which two-thirds of Americans regard as having too much power. Jurors may also struggle to grasp the nuances of antitrust laws. Another explanation is, ironically, that Google has tried to make its mobile software too open. Anyone can use Android’s open-source code free of charge to create their own OS. By contrast, Apple’s customers and developers know that it controls all aspects of the iPhone. Being locked in Apple’s walled garden may be more palatable if consumers know what they are getting into, but it would be less so if limits are imposed by the maker of just the operating system, which it claims is open.

The verdict may influence two other lawsuits against Google by America’s Department of Justice. The first went to court in September. It focuses on Google’s deals to ensure it is the default search engine on various devices, including Apple’s and web browsers. Such arrangements cost it $26 billion in 2021. The second is likely to begin next summer and looks at Google’s advertising business. The judge in the Epic case will decide on a remedy early next year. One possibility is for app developers to be freed from Google’s billing system. Last year, South Korea forced Apple and Google to enable alternative payments. The EU’s new digital law has similar provisions. This may be making the app store economy more competitive — especially for games. Microsoft, which has just concluded its $69 billion acquisition of Activision-Blizzard, a big game developer, is planning its own app store for games. Epic already has one for PCs. Riot Games, a rival, may launch its own.

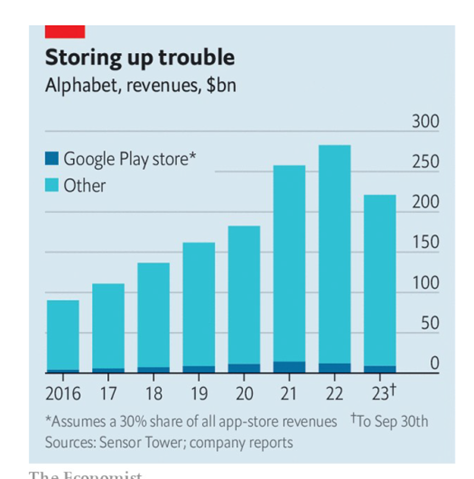

The tech giants do not like this one bit. According to Sensor Tower, a research firm, people around the world will spend about $160 billion on apps this year. Google’s and Apple’s commissions account for perhaps five per cent of each firm’s overall revenue. Operating margins for both app stores are thought to be over 70 per cent, according to testimony in the two court cases. (Google argued in court that this figure does not account for some app-store costs, such as research and development.) That is much higher than the overall margins of 26 per cent for Google and 30 per cent for Apple last year.

Google is already seeing its Play store revenues dip, reckons Sensor Tower (see chart). So, neither firm will give up without a fight. Google is challenging the jurors’ decision at an appeals court, where a panel of judges will hear the case. Apple is appealing against the payments ruling in its Epic case. Both are finding ways around rules like those in South Korea, where they let in alternative billing methods — and promptly slapped a commission of up to 26 per cent on any sum paid using them.

Let’s continue to talk about Google and why some people are upset with it. Recently, Google had a big problem with something called “antitrust”, which was mentioned above. This is when people think a big company, like Google, is being unfair and not playing by the rules.

So, what happened is that some important people, like judges, said that Google did some things that weren’t right. They told Google was too powerful and didn’t give other companies a fair chance. Imagine you have a game, and one player keeps changing the rules so they always win – that’s a bit like what Google was doing.

Now, you might wonder, “Why does this matter to me?” Well, it’s because Google is like a big boss in the world of apps. When you want to find and download apps on your phone, you probably use the Google Play Store. But because of what Google did, it made it harder for other companies to make cool apps and for you to have more choices.

Think of it like going to a candy store, and the owner only lets you buy one type of candy. You might want different flavours, but the owner says, “No, you can only have this one.” That’s kind of what Google was doing with apps – not letting you have as many choices as you could.

So, this defeat for Google means they have to change their ways. It’s like the owner of the candy store getting in trouble and being told, “You have to let people choose what they want.” This is good news because it means more fairness and more chances for other companies to make fun and useful apps for you.

In sum, this is about making sure everyone has a fair shot in the app world. It might not sound like a big deal, but it’s like making sure the candy store has all the different candies you love, not just one!

Reference: The Economist Magazine 2023.12.16